We Can End the Opioid Epidemic For Pennies A Day

A once popular remedy is being used to solve opioid problems and can be used more in the United States. Share this article to friends, politicians, EMS personnel: let's start a conversation.

Introduction

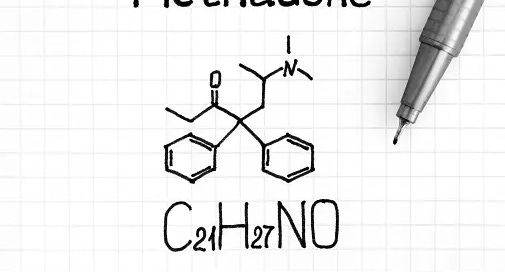

We have a problem in American society. Highly addictive substances of the opium variety, the gooey substance found in the flower, and the more potent heroin and lethal synthetic fentanyl are plaguing our streets and killing people by the tens of thousands each year. We will be faced soon with a reckoning: a national crisis, public health emergency, and the resurgence of draconian punishments. We will incarcerate addicts only to release them straight back into a world packed with abundant, addictive substances. But what if there was another way? What if there was a substance, for pennies a day, that could help somebody live with, and function with a heroin addiction? What if this substance could keep their addiction at bay—safely, under medical supervision. What if this could reduce people dependent on street drugs, minimize the drug market, reduce petty and violent crimes that rise from the drug trade, and what if it could give people addicted to this vile substance a fighting chance? Well, there is a substance, and it is something that I am ashamed to admit I knew little about until recently. It is called Methadone, and its potential to pull us out of this opioid epidemic, for pennies a day, blew my mind.

A Brief History of Opium

The book, Dreamland, written by Sam Quinones, is perhaps the most important book for explaining drug use and addiction in the United States. It does a fantastic job of following the history of the drug, opium, which we must understand before we can understand the solution. Opium is a drug that is found within the opium poppy and was first known to be grown along the shores of the rivers in Mesopotamia. It has been long renowned for its benefits, and long feared for its side-effects. Inside the flower’s core, a “pod” can be drained to access the euphoric substance inside. The Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Arabs all grew and expanded the drug's reach across the world. It was a plant that was known across the ancient world for spreading tremendous joy; it was also known for causing horrendous fatalities (overdoses) and devastating addictive tendencies.

Opium was vital for a species that is quick to conflict. Soldiers, with increasingly brutal weapons of war, began to depend on it as their flesh was mutilated in increasingly dynamic ways. During the American Civil War, opium poppies were planted across the United States in an effort to keep up with the rampant bloodshed. From there, the United States got its first taste of a drug addicted society. Other groups, including Chinese immigrants, brought opium to the United States (that the United States and Great Britain initially sold to them) and furthered its reach.

Because opium’s benefits were so important for managing pain, doctors everywhere tried to find a way of making opium non addictive. American doctors failed, the best they could do was heroin. Heroin, they thought, could work to be non addictive, and without options they went with it. Of course, it was terribly addictive and led to a prohibition on drugs, with governments relentlessly targeting those who had been addicted to it, leading to a war on drugs fought all the way in the 1870s.

The Race For a Non Addictive Painkiller

When Nazi Germany was preparing to wage all-out war across Europe, they needed to become medically independent from the rest of the world. The hundreds of wars that had been fought over the last century had made armies realize the importance of pain medication, and existing remedies came with costs. The Germans had also, in fact, been the first to isolate Morphine from the opium poppy in the early 19th century, which they named after the Greek god for sleep, Morpheus. Their scientists took this earlier discovery further and created a pain medication that came without known side-effects of morphine. It was a strong narcotic, addictive, but in a different way than the morphine molecule. It was addictive, but peculiarly enough the addictive tendencies didn’t expand overtime as they commonly do with drugs; think of it like this, you're addicted to smoking one full cigarette a day, without ever wanting a second. This miracle drug, and the solution to Nazi Germany’s problem, was called Methadone.

After 1947 US doctors took over research on the drug Methadone. Doctor Vincent Dole led a team of US doctors in recognizing the potential for this drug to be used in medical settings for treating addiction. Methadone was satisfying the craving of opioid addicts, but their reactions to it perplexed Dole. He found addicts on Methadone to be tolerable: they were not perpetually obsessing over their next fix: they could function relatively normally. As long as they received the right dose of Methadone, they were fine to go throughout their day, without needing more highs. This was different from drug addicts he had worked with who were on heroin, who he noticed were singularly fixated on their next dose. I can anecdotally attest, having worked with people with past heroin addictions. I have been told that after a time there is no joy from using heroin, but the withdrawal symptoms were so nightmarish that to not inject was a terrifying prospect, worth furthering a life of crime to support their habit.

Doctor Dole believed that one dose of this Methadone per day would allow addicts to function normally in society. Of course, like any reasonable doctor of his time, he believed that Methadone should be accompanied by rehabilitation and 12-step programs. However, we know that rehabilitation is a fluid, often long-term process; not everyone will be ready for rehabilitation at the same time, and Methadone was something that people could either wean off of, or stay on and use as a crutch for the rest of their lives–something Dole believed was the best option for those who could not function without it.

In the 1970s, we saw what happened when a regulated and safely distributed narcotic with the possible benefits of Methadone was distributed widely. Reductions in crime followed. There were less dirty needles on the streets. Crime, the obvious side effect of rampant drug dealing, declined. The addicts themselves transitioned from lives of crime to support their habits, to functioning adults who could maintain jobs and support their families.

Doctor Dole’s strategy was effectively to keep heroin addicts on Methadone for the rest of their lives if they needed to. It was cheap, costing around 50 cents for a daily dose. There was another school of thought that it should only be used for a time, with rehabilitation being the primary focus. Which school of thought won? Neither. Because where there are drugs in the United States, there is a chance for profits. What was at first a remarkable solution to a rampant opioid problem became a market ploy for drug dealers. Privatized Methadone clinics increasingly reduced rehabilitation and 12-step programs, and were increasingly viewed as neighborhood drug dealers, selling Methadone doses for upwards of thirty-times its production cost.

Instead of the therapeutic dose to get a person by for a day, they would hand out enough for a person to make it a few hours. By the time their dose had worn off, clinics would be closed for the day, and drug dealers took to hanging around the clinics to sell to desperate customers. Because of poor dosing and an increasingly expensive, drug-centric model, Methadone went from a miracle cure to a drug used interchangeably with heroin throughout the day.

Coming Back To Methadone: Modern Research

The next few sections will examine research from the National Institute of Health. In Hong Kong, in response to rising drug addiction, Methadone became a solution for helping addicts with their heroin addictions. One of their primary focuses was on reducing HIV infections through shared needles, and at 12 cents per person per day, Methadone seemed like a cost-effective solution. Starting in 1972 the ongoing study has shown outstanding results.

People could afford the 12 cent price per daily dose.

The clinics were accessible, open early in the morning and staying open late. The facilities were secure, patients could access methadone easily (no pre-conditions), and it was in a judgment free environment.

They focused on a therapeutic dose of at least 60 milligrams per day, noting that less than this led to an increase in alternative drug use.

This Will Blow Your Mind: Statistics From Australian, Iran, Others

Methadone in prisons in Australian, Canadian, Iranian, and other regions showed tremendous results for reducing drug dependency. Drugs are widely available in prison, and inmates in these countries who had started Methadone had an 80% rate of using heroin in the last month prior to treatment. After just four months, however, the usage rate of heroin dropped to just 25%. They further found that:

These inmates were less likely to return to prison if they were able to stay on Methadone post-release.

They were less likely to relapse into heroin after release.

Important: “at a maintenance dose, it does not induce euphoria”

I mentioned earlier anecdotal evidence that heroin addicts no longer feel much from heroin, but simply rely on it to avoid devastating withdrawal. The people on the street reacting violently who are chronic addicts, well, they are using street substances and in the age of fentanyl, who knows what they are using. However, this fantastic research that I have been touching on notes that people who are addicted to Methadone, when they can access it at therapeutic levels, will be free from withdrawal, and able to function normally without being high. This is no doubt very important for those who are against distributing narcotics, and I highly recommend highlighting this in meetings about expanding Methadone availability.

We Need To Spread the Word: This Is Working, And It Must Be Promoted

A poll recently came out from Axios that opioids are perceived by the public to be the largest threat in the United States. If you are a politician, police chief, medical professional, scholar, activist–it doesn’t matter, you need to think about this. This could save lives, particularly if it is used properly. We need to take up this fight as a society, collectively. In the 1970s they could do this right. 50 years later we have some of the highest addiction rates ever. Why? It appears that we are not using all of our tools as effectively as we could be. This is working in many societies, but we understate or ignore its value here.

Concerned people across the United States are afraid of opioids coming to their communities. They fear their children getting addicted and they should. For a sizable portion of human history there has been admiration and fear of the power and addictiveness of opioids. Suddenly, with scientific ingenuity, there is a cure and we need to use it. We need to revisit research by Doctor Vincent Dole that pointed to Methadone as being a long-term crutch for heroin-dependent people.

We need to carefully educate the public on this. Methadone clinics, revamped, with better public education, can work. They can be supervised, federally regulated, secure, and provide the right therapeutic doses that, referencing information above, will not lead to the state providing euphoric highs, but medication that can save lives, reduce crime, reduce overdose deaths, reduce HIV and other infections. We need this, and for fifty cents per-person-per-day, we can work to end our opioid epidemic.